Typology and Theory of Remotivation

Do German butterflies fold lemons? One of the things Professor Rüdiger Harnisch examines in this project is why utterances are loaded with additional meaning.

The German Research Foundation is funding the project ‘Typology and theory of remotivation’ of the Chair of German Language, which is held by Professor Rüdiger Harnisch. The primary question is how and why utterances are given additional meaning (sense-seeking) and are made more transparent in their composition than they are would normally be (structure-seeking).

Linguistic signs are seen as being arbitrary, rather than motivated. Their visible and audible form is not generally a direct expression of their meaning, although exceptions can be found in onomatopoetic words, such as ‘cough’, folk etymologies like ‘hamburger’ (which has nothing to do with ham but everything with Hamburg) and transparent constructs such as ‘twenty-three’, as an aggregate of ‘twenty and three’.

An abundance of form creates its own meaning

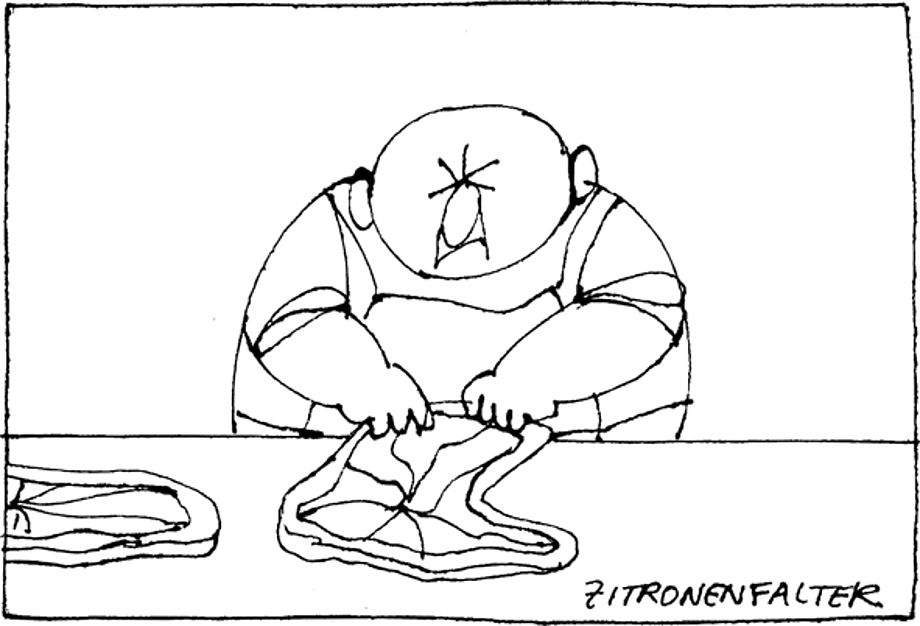

The projects aims to show that speakers find, and even invent, many additional relationships between form and meaning as they come across utterances: it is this that ‘remotivation’ describes. For instance, German children often falsely interpret words such as ‘sauber’ (clean) as the comparative of ‘saub’ – clean-er – although the form ‘saub’ does not exist in German. Similarly, the meaning(s) and structure of words such as ‘Zitronenfalter’ (brimstone butterfly) can be reinterpreted as ‘a person who folds lemons’, as shown in the picture to the right (photo: Fotolia, www.paulflora-rechte.com). Of course, the word ‘Falter’ is not derived from ‘falten’ (to fold) but related to ‘flattern’ (to flutter) and, as a noun, means butterfly, whereas the ‘lemon’ refers to the colour of its wings rather than the fruit itself. This is an example of an abundance of form being filled with meaning.

Moreover, the opposite is also within the scope of the project: meaning that seeks additional form. For instance, with the adjective ‘fisk-al’, German tries to give it the German hallmark of an adjective, rendering it ‘fiskal-isch’; or ‘Keks’ (biscuit), which is already derived from an English plural – cakes – is then redundantly embellished with a German plural ending, resulting in ‘Keks-e’. A third phenomenon that is analysed in this project is where one sense requires another, i.e. where the true meaning can only be derived if an utterance is interpreted in its context rather than literally: Giving the literal answer ‘Yes, indeed’, usually meant humorously, when asked ‘Do you have the time?’ – the contextual meaning, of course, being ‘What time is it?’ – is one example of this. This also works the other way round, where a literal meaning is supplemented with additional meaning from the listener’s or reader’s knowledge: ‘mandatory’ and ‘compulsory’ have the same meaning, but as the former is used far more often in American English than in British English, there is indirect information that someone using ‘mandatory’ likely comes from North America.

A multitude of linguistic phenomena

The team of researchers intend to categorise the diversity of linguistic phenomena of this type to construct a theory of remotivation, which does not exist as such in German linguistics; while many disparate phenomena described above have already been analysed, there has been a dearth of detailed descriptions of the underlying similarities of these types as well as their characteristic differences.

| Principal Investigator(s) at the University | Prof. Dr. Rüdiger Harnisch (Lehrstuhl für Deutsche Sprachwissenschaft) |

|---|---|

| Project period | 01.10.2015 - 30.09.2018 |

| Verlängert bis: | 30.09.2019 |

| Website | http://www.phil.uni-passau.de/index.php?id=8274 |

| Source of funding |  DFG - Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft > DFG - Sachbeihilfe |